From classical dance in Lorraine to Applied Arts in Paris: a multidisciplinary technical education.

“Let us imagine a body full of thinking limbs,” wrote Pascal in his Pensées. Believing that intelligence is not the sole province of the brain but of the entire body, Eve is passionate about the relationship between body and mind, and deeply interested in how physical awareness nurtures creativity and heightens consciousness. For example, in his improvisation technique videos, choreographer William Forsythe connects the movements that compose his repertoire to geometric forms, illustrating the link between dancing and drawing.

In the tradition of the artist-engineer, Eve’s work lies at the intersection of sculpture, performance, dance, architecture, and design. Through her white biomorphic sculptures with rounded forms and her live performances on mobile structures—playing with weight and counterweight—she speaks about consciousness. Raised by parents who never expected their daughters to conform to stereotypical notions of femininity, Eve was free to express her early fascination with simple mechanical laws through construction games and to climb to the tops of trees without fear. In her visual work, she explores themes such as presence, trust, positive risk-taking, balance, and the relationship between our bodies and the Earth’s gravity.

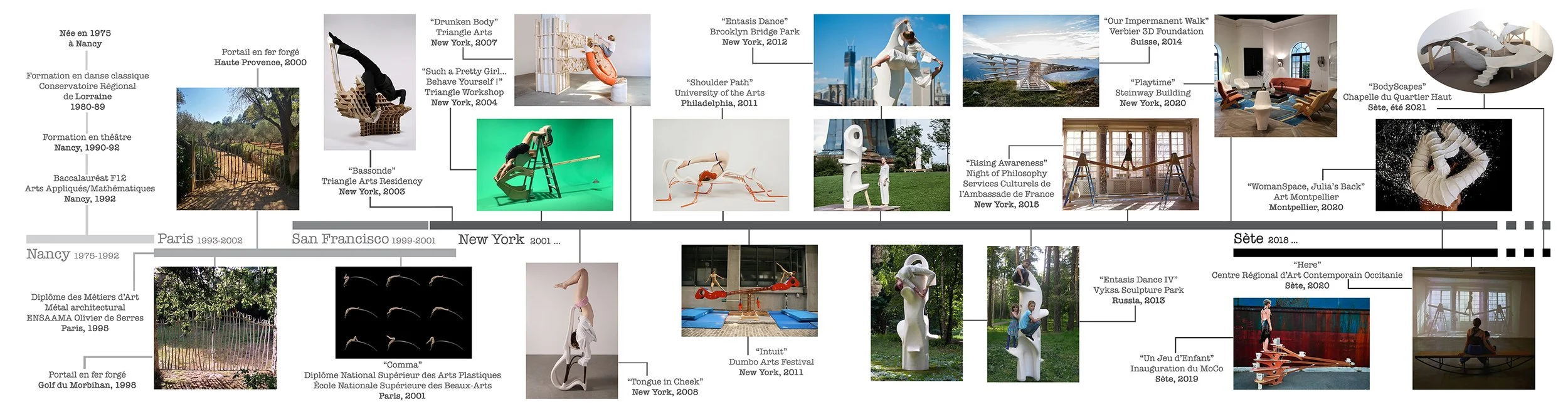

Born in 1975 in Nancy—the cradle of Art Nouveau and the home of architect Jean Prouvé—Eve is an heir to a tradition of thought that unites art and function. Her artistic approach is as multidisciplinary as her education was. From kindergarten through middle school, alongside an exemplary general academic path, she received intensive training in classical dance and music at the Lorraine Conservatory, notably through an adapted schedule during secondary school. Upon entering high school in the F12 track, a program combining applied arts and mathematics, she studied technical drawing, perspective techniques, and art history. For her baccalaureate—with honors as a laureate—she designed a stage set using mobile platforms to pull the actresses playing the Undines in Jean Giraudoux’s play.

In Paris, after ranking first in the entrance exam, Eve joined the metal workshop founded by silversmith Serge Mouille at the École Nationale Supérieure des Arts Appliqués Olivier de Serres. During her studies, she won first prize in an art and design competition at the Louvre Museum for the conception and fabrication of a Mahjong set designed for both sighted and non-sighted players. For her Diplôme des Métiers d’Art, awarded with highest honors, she created motorized kinetic works inspired by the mechanics of early flying machines. With invaluable technical autonomy in hand, Eve became eager for theory, research, and travel.

Sculpture in Paris and performance in San Francisco: the emergence of an art form rooted in the moving body.

She found her place at the Beaux-Arts de Paris in the transdisciplinary studio of artist Tony Brown, where her reflections on the relationships between body and mind, and between object and body, began to take shape. In this regard, inspiring workshops with artist Rita McBride further paved her path. Fascinated by the brain’s extraordinary powers, Eve spent six months working with an MRI of her own brain, modeled in 3D in collaboration with an engineer from the medical imaging laboratory at the neurology center of the Quinze-Vingts Hospital. In another, more technical vein, she also undertook the fabrication of wrought-iron gates in one of the last industrial forges in France, located in Pantin, in partnership with the school.

In 1999, as the recipient of the Colin Lefranc grant, she spent a year on a university exchange at the San Francisco Art Institute in California. There, in contact with artists Paul Kos, Tony Labat, and Sharon Grace in the New Genres department, she became acquainted with performance art. Her very first action, Hanging, took the form of a video in which she is seen hanging upside down from a bus rail, observing the reactions of passengers as they crossed San Francisco—a shift in perspective shared by artist Gordon Matta-Clark, who also loved to suspend himself.

Alongside her studies, Eve was noticed for her skill in drawing, and the director of a private crafts school in Paris (AFEDAP) hired her as a perspective instructor. She specialized in anamorphosis techniques, which she still finds fascinating and which continue to enrich the way she perceives forms in space. Years later, she was invited as a professional contributor by the architecture magazine The Funambulist to write an essay on a groundbreaking new technique of representation, in which she compared this research to that of architect Frederick Kiesler, who was deeply concerned with the concept of infinity.

In 2001, the defense of her diploma at the Beaux-Arts de Paris sparked a debate: what was the artwork—herself or the object? The discussion ended without a clear conclusion. It is true that, at the time, there were few conceptual tools to sustain such an exchange. Major contemporary platforms and exhibitions devoted to this question had not yet taken place. Among them were the Performa biennial, created in New York by critic RoseLee Goldberg in 2004 to address this very gap, or Dance, a collection of texts by choreographers and artists co-published in 2012 in the “Documents of Contemporary Art” series by Whitechapel Gallery (London) and MIT Press (Cambridge).

From performative assemblages in New York to machined structures in Europe: balancing acts between art and design.

Eve lived full-time in New York from 2002 to 2018. In the spirit of Trisha Brown, she began to inhabit the streets and rooftops of Brooklyn with spontaneous performances. The structures—made from everyday objects assembled like balancing mechanisms—allowed her to perform acrobatics safely, engaging in actions that challenged preconceived notions of behavior. Her motivation is to push the limits of both her own balance and that of the artwork, creating a unique metaphor with each new assemblage.

The distribution of forces, weights, and counterweights is not calculated mathematically. Eve estimates them intuitively by manipulating 1:10 scale models. From a neuroscientific perspective, intuition could be seen as a form of intelligence too rapid for consciousness. In any case, her structures function from the very first tests in the studio. Indoors, within galleries, or outdoors in urban spaces, the public first encounters elements arranged on the ground. Then, she assembles each piece in a precise sequence. Gradually, the structure takes shape and arouses curiosity. Meaning emerges at the moment when the body engages in balance.

Eve is regularly invited to create inaugural performances, such as Rising Awareness for the Nuit de la Philosophie organized by Mériam Korichi in New York in 2015, echoing a lecture by Barbara Cassin and captured in the pages of The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal; or 100 Artists in the City, a project by Nicolas Bourriaud for the opening of MoCo (Montpellier Contemporain) in 2019.

Throughout her journey, dancers have shown great interest in her living structures. In response to their enthusiasm, she decided to open her practice to professionals. Around the same time, around 2010, various international institutions began inviting her to produce works in public spaces. This required rethinking her constructions for permanent outdoor installations. In the Swiss Alps in 2014, at the Verbier 3D Foundation, Eve created a series of stair-like balancing structures titled Our Impermanent Walk. She fabricated them in aluminum with machined stainless steel mechanical components, designed to withstand weather conditions and interact with the pure, high-altitude light. The sculpture is installed in the foundation’s park at 2,400 meters above sea level. Its architectural design responds to the contours of the surrounding mountains.

In Brooklyn, the search for harmony between body, mind, and matter: biomorphic sculptures and drawings.

At the same time, Eve developed another body of purely sculptural work in which, although the moving body is always at the very origin of the piece, live performance occurs later or remains concealed within the process. From a strictly formal perspective, her biomorphic sculptures function perfectly without any physical intervention. Because these objects are shaped from the spatial coordinates of a body with its unique qualities, they possess an intrinsically organic and sensual nature. Their origin invites inquiry. What is valuable in the performance—or in its documentation—is that it brings her creative process to light. In 2012, within the exhibition Blur: Six Artists & Six Designers in Contemporary Practice at the University of the Arts in Philadelphia, her work Shoulder Path drew the attention of numerous critics.

In Title Magazine, writer Jeffrey Bussmann noted: “In the photograph, the artist’s body forms, frozen in motion, act like a semaphore language. Looking again at the sculpture in the gallery, I could appreciate how its design was dictated by her body unfolding in space, as if she had left an impression in clay.”

In his article Designing Gravity, architect, theorist, and The Funambulist editor Léopold Lambert wrote: “Eve’s work is an ode to the search for the body’s balance—one that must not fall, of course, but must also find the varied points of gravity within the design so that it, too, does not tip over. (…) What the body does to the object is, of course, conditioned by the design, but it can also consist in the subversion of those conditions, or in the sum of behaviors that exceed the original range of actions imagined by the artist.”

Eve would say that “she choreographs her sculptures and drawings.” Not only are her forms conceived in relation to the moving body, but she also handles her pencils and machine tools with the heightened awareness of a dancer. In the studio, she executes each gesture with intention. Beyond her classical dance training at the conservatory, it is also a decade of dedicated practice in the Brazilian martial dance Capoeira—in France, the Netherlands, Germany, Hungary, and the United States—that continues, consciously or not, to influence her formal choices. Another source of inspiration within the popular culture of martial arts is an actor like Jackie Chan in his early years in China, unmatched in the skill and creativity with which he moves his body and objects. Indeed, the physical and spiritual training of Shaolin monks remains an inexhaustible wellspring for exploring the relationship between object, body, and mind.

Generating forms that make bodies and minds dance: the series of totemic sculptures entitled Entasis Dance.

Within the dynamics of weight transfer, Eve is particularly sensitive to the approach of the dancer and choreographer Steve Paxton, with whom she had the opportunity to exchange in New York about the origins of contact improvisation. Within the Judson Dance Theater, the group explored movements that generate joy. The dancers drew on the image of a child leaping impulsively into an adult’s arms. Filmed in 1979 and commented on by Paxton, the video Fall (Chute) perfectly describes the underlying principles of contact improvisation that are present in her work. Through heightened awareness, the dancers’ bodily envelope becomes a surface fully visualized in space through the sense of proprioception. With controlled weight transfers, the body can transform an accidental movement into a danced gesture.

Paxton’s approach, the collaborative work between Isamu Noguchi and Martha Graham, as well as the wooden training structures of the Wing Chun martial art, form the intertwined core of inspirations for her series of white totems entitled Entasis Dance. In the studio, Eve moves around a cylinder three meters high. With her eyes closed, she visualizes a body in motion intersecting the volume. No material is added; every preserved hollow becomes a protrusion. Temporarily exhibited at Brooklyn Bridge Park in New York in 2012 during the construction of the Freedom Tower, the sculptures are now installed in parks in the United States and Russia. Commissioned and exhibited by the Musée Régional d’Art Contemporain Occitanie, Entasis Dance V was acquired by the city of Sète in 2022.

On special occasions, public or private, Eve invites performers to move within her space–body devices, as the chief curator of the Noguchi Museum likes to call them. For the duration of a performance, the movements of dancers dressed in white costumes—created by Anna Finke, costume designer for Merce Cunningham in the United States, and later developed by Catherine Sardi in France—offer a palette of gestures that animate the sculptures like living architectures.

A detour through cognitive sciences, followed by a return to France and the development of new works opened to the public.

Between 2015 and 2018, Eve slowed her artistic production in order to care for her father, who was suffering from Lewy body dementia. Inspired by Norman Doidge’s book on the history of neuroplasticity, The Brain That Changes Itself (Les Étonnants Pouvoirs de Transformation du Cerveau), she undertook to help her father retain autonomy until the end of his life. She became particularly interested in the work of scientists Paul Bach-y-Rita on brain plasticity and V. S. Ramachandran on behavioral neurology. It was through these intensive readings that she became aware of the sense of proprioception.

Thanks to this detour into science, she acquired the intellectual tools to understand what has always intuitively driven her. Eve spoke of coordination and balance, while knowing that she was touching on something far deeper. In his collection of medical case studies The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, Oliver Sacks, the eminent British neurologist, concludes that the sense of proprioception may be the sense closest to our sense of self.

In a text devoted to her work, the writer Philippe Saulle offers a fine description of it: “(...) We often speak, somewhat foolishly, of concentration—of staying focused. Perhaps this notion is relevant when thinking or learning, but it no longer makes sense when we are doing what our body knows. (...) Bending down to pass under a beam without hitting oneself is the unconscious result of our proprioceptive sense. A sense of space, of the body within that space, of its position, (...) of its vibrations. Régine Lacroix-Neuberth, mother of technesthesia, wrote: ‘Presence depends on an individual’s perception of their proprioceptive sensations.’ To praise proprioception is not to oppose transparency, but to underscore the freedom it offers our bodies when they are in danger.”

Today, Eve Laroche-Joubert opens her practice to a much broader audience by developing accessible forms, conceived to be traversed, inhabited, and experienced corporeally. This evolution is notably embodied in her latest bird-observatory sculpture project, featured on the front page of Le Monde, which she dedicates to young Talya, a wheelchair user living in the village of Vic-la-Gardiole in the south of France, where the work will be installed before spring 2026. In parallel, she continues her sculptural research centered on the body through forms devoid of any functionality, thereby affirming a fertile tension between potential use and formal freedom, between shared experience and the poetic autonomy of the object.